Table of Contents

HOMOPHONES and HOMONYMS

|

In Gene Barretta’s Dear Deer (Square Fish, 2010), a picture book crammed with homophones, Aunt Ant has moved to the zoo and writes letters describing her experiences to Dear Deer. (“Wait until you HEAR what goes on over HERE.”) All the homophones are emphasized in capital letters. For ages 4-7 |

|

Brian P. Cleary’s How Much Can a Bare Bear Bear? (Millbrook Press, 2007) is a zany rhyming look at homonyms (words with the same spelling but different meanings) and homophones (words with the same pronunciation, but different spelling and meanings) for ages 6-10. For more on homonyms and homophones by Cleary, see A Bat Cannot Bat, a Stair Cannot Stare (2016). |

|

Marvin Terban’s Eight Ate (HMH, 2007) is a “feast of homonym riddles.” “What is an animal with a rough-sounding voice that cowboys ride?” “Hoarse horse.” For ages 4-8. |

|

Fred Gwynne’s now-classic The King Who Rained (Aladdin, 1988) begins with a play on “reigned” and “rained” as the king, in robe and crown, floats like a cloud in the sky, raining on a little girl who holds a yellow umbrella. Other homonymous titles by Gwynne are A Chocolate Moose for Dinner (Prentice-Hall, 1987) and A Little Pigeon Toad (Aladdin, 1990). |

WONDERFUL WORDS: Nonfiction

|

Rosalie Baker’s In a Word: 750 Words and Their Fascinating Stories and Origins (Cricket Books, 2003) is organized into 16 chapters (sample titles are “Math Magic and Science Synergy,” “Glorious Gizmos and Great Grub,” “Awesome Archaeology,” and “Fantastic Foreigners”) and is crammed with interesting tidbits. (The word “candidate,” for example, comes from the Latin meaning “clothed in white,” since persons running for political office in Rome took great care to whiten their togas.) For ages 9 and up. |

|

Edited by Erin McKean, Totally Weird and Wonderful Words (Oxford University Press, 2006) is a cartoon-illustrated compendium of hundreds. (Spanghew: to cause a frog or toad to fly into the air.) A plus for all vocabularies. |

|

By Paul Fleischman, with wonderful illustrations by Melissa Sweet, Alphamaniacs (Candlewick, 2020) is a collection of 26 mini-biographies of linguists, etymologists, and wordsmiths who have approached language, letters, words, and books in unusual, bizarre, and thoroughly entertaining ways. Meet the inventor of Klingon and the writer whose novella uses no vowels but e. For ages 10-14. |

|

By Paul Anthony Jones, The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities (Elliot & Thompson, 2019) has a strange and forgotten word for every day of the year, starting on January 1 with qualtagh – a word which means, appropriately enough, the first person you meet on New Year’s Day. For ages 13 and up. |

|

Robert Macfarlane’s The Lost Words (Anansi International, 2018) had its beginnings when the author discovered that the new edition of the Oxford children’s dictionary had dropped a long list of nature words, such as acorn, bluebell, fern, raven, and willow. This beautifully illustrated book is a “spell book,” designed to bring those words back. For all ages. From Brainpickings, see this wonderful review of The Lost Words. |

|

Renowned wordsmith Richard Lederer has published numerous books on the outrageous oddities of English. His Crazy English (Gallery Books, 1998), for example, is an irresistible overview of the language. (What’s the longest word in English? The most beautiful word? How many different kinds of phobia words are there? And why is English spelling so weird?) For teens and adults. |

|

In Ben Blatt’s Nabokov’s Favorite Word Is Mauve (Simon & Schuster, 2018), data analysis meets literature – how do writers actually use words? (“On average, for every 17 words Hemingway wrote, one of them was an adverb.”) For teens and adults. |

|

E-prime is a dialect of English that eliminates all forms of the verb “to be,” arguing that this enhances clarity and critical thinking. Give it a try – “to be” is surprisingly difficult to give up. |

WONDERFUL WORDS: Fiction

|

In Peter H. Reynolds’s The Word Collector (Orchard Books, 2018), while some people collect coins or stamps, Jerome collects wonderful words. For ages 4-8. |

|

In Rebecca Van Slyke’s Lexie the Word Wrangler (Nancy Paulsen Books, 2017), cowgirl Lexie – complete with boots, hat, and lariat – has a talent for word wrangling, growing letters into bigger and bigger words, and hooking words together: “She could take a stick of butter and a pesky fly…and make a beautiful butterfly.” But then a word rustler comes to town. For ages 4-8. |

|

In Kate Banks’s Max’s Words (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006), Max’s two older brothers collect stamps and coins, but Max collects words – cutting them out of magazines or copying them out of the dictionary. His brothers laugh at him – but eventually, as Max shares his words, the three boys collaborate, using Max’s many words to create a story. For ages 4-8. |

|

Paul M. Levitt’s The Weighty Word Book (University of New Mexico Press, 2009) consists of 26 short stories centered around a “weighty” word for each letter of the alphabet, from Abasement and Bifurcate to Juxtapose, Scintillate, Ubiquitous, and Zealot. For ages 8-12. |

|

In Roni Schotter’s The Boy Who Loved Words (Schwartz & Wade, 2006), Selig is a word collector, who writes his finds on slips of paper and carries them in his pockets. Finally he attaches his words to a tree – where some of them blow into the hands of a needy poet – and Selig discovers that his goal in life is to share wonderful words with others. For ages 6-9. |

|

Edited by Lee Bennett Hopkins, Wonderful Words (Simon & Schuster, 2004) is a collection of poems about the many aspects of words, among them David McCord’s “How to Say a Long Hard Word” and Pat Mora’s “Words Free as Confetti.” For ages 6-11. |

|

In James Thurber’s truly wonderful The Wonderful O (Penguin Classics, 2017), pirates Black and Littlejack – the former of whom has hated the letter O ever since his mother was fatally wedged in a porthole – land on an island and proceed to ban the letter O. It’s a magical exercise in language – and a heartwarming tale of overthrowing tyranny. For ages 8-12. And up. |

|

In Mark Dunn’s Ella Minnow Pea (Anchor, 2002), Ella lives on the island of Nollop – named for Nevin Nollop, inventor of the phrase “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.” When letters of this phrase begin dropping off Nollop’s memorial statue, the island’s ruling Council takes it as a sign that the lost letters must be banned altogether. The book is written as a series of letters, which become increasingly impossible to write as more and more letters of the alphabet bite the dust. For ages 13 and up. |

|

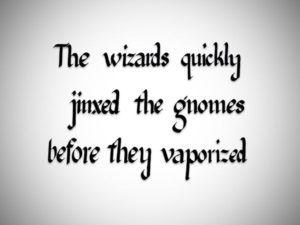

A sentence that uses every letter of the alphabet – like “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog” – is called a pangram. See many more here. (Invent your own!) |