Typically philosophy is a college-level discipline, but there’s every reason, given the opportunity, to introduce it earlier. Kids from a very young age are fascinated by philosophy’s fundamental questions about the world and ourselves, and exploring these helps develop critical and creative thinking skills and allows kids to hone and express their own opinions. It’s also useful to discover that there are many questions to which there are no definitive answers. (But that doesn’t mean we can’t keep trying to find some.)

“To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive.” Robert Louis Stevenson

Table of Contents

General

= |

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy includes an overview of approaches to teaching philosophy to kids, along with an extensive bibliography of books and articles. |

|

The University of Washington’s Center for Philosophy for Children includes a wide range of lesson plans, games, activities, and exercises for kids of all ages. Included , for example, are ideas for teaching philosophy through literature, using over 100 different children’s books, and activities dealing with environmental ethics, ethical dilemma, philosophical perspectives in the news, reasoning and arguments, Plato’s Cave, and much more. |

|

Dialogue Works, along with philosophy training courses for teachers and facilitators, offers a list of free resources, notably “HomeTalks:” activities and discussion suggestions on a wide range of topics, such risk and bravery, prejudice, gratitude, play, and conflict. |

|

Thomas Wartenburg’s Big Ideas for Little Kids (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014), subtitled “Teaching Philosophy Through Children’s Literature,” shows how to generate philosophical discussions using popular children’s books. All major branches of philosophy are covered – ethics, social and political philosophy, philosophy of the mind, environmental philosophy, logic, epistemology, aesthetics, and the philosophy of language – all through such works as The Giving Tree, Knuffle Bunny, and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Teaching units for dozens of children’s books are available at the accompanying website – a terrific resource. |

|

In Marietta McCarty’s Little Big Minds (Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2006), each chapter provides background information on the featured topic, an overview of influential philosophers in the field, resources, teaching tips, discussion questions, and exercises. Chapter titles include “Friendship,” “Responsibility,” “Happiness,” “Justice,” “God,” and “Freedom.” |

|

Socrates Café by Christopher Phillips (W.W. Norton, 2002) is the work of an amateur philosopher attempting to start a grassroots philosophy movement. He does this by hosting “Socrates Cafes” – get-togethers in coffee shops, schools, nursing homes, libraries, or living-rooms where people meet for the purpose of asking questions and thereby exploring, clarifying, and expanding upon their opinions and beliefs. The book consists of multiple accounts of homespun philosophy groups, in which children and adults pursue answers to such questions as “What is wisdom?” “What is freedom?” “What is belief?” “What is happiness?” “What is good?” At the end of the book, Phillips includes a glossary of philosophers, suggestions for further reading, and general instructions for organizing and facilitating your own Socrates Café. |

For Younger Kids

|

For preschoolers, Duane Armitage’s Big Ideas for Little Philosophers series (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2020) is a collection of simple board books introducing the thought of prominent philosophers to the youngest readers. Among the titles are Truth with Socrates, Happiness with Aristotle, Imagination with Rene Descartes, Love with Plato, Kindness with Confucius, and Equality with Simone de Beauvoir. |

|

Wittgenstein’s Rhinoceros by Francoise Armengaud (Diaphanes, 2016) is one of the Plato & Co. series, picture books using events in the lives of prominent philosophers to illustrate their ideas and theories. Other titles in the series include Professor Kant’s Incredible Day, Mister Descartes and His Evil Genius, and Kierkegaard and the Mermaid. For ages 6-10. |

|

M.D. Usher’s Wise Guy: The Life and Philosophy of Socrates (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2005) is a picture-book introduction to the contentious Greek philosopher who emphasized the importance of the examined life and famously pointed out that “All I know is that I know nothing.” The simpler version of Socrates’s life and thought is presented in the main text; trickier bits, for older readers, appear in sidebar scrolls. Usher, a classics professor from the University of Vermont, has a knack for distilling the complicated for a young audience. For ages 7-11. By the same author, see Diogenes (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2009), in which the main philosophical character appears as a very thoughtful dog. |

|

Sharon Kaye’s Big Thinkers and Big Ideas: An Introduction to Eastern and Western Philosophy for Kids (Rockridge Press, 2020) is a colorful and engaging introduction to four main branches of philosophy: reality, knowledge, ethics, and logic. Chapter titles are “What is philosophy?” “What is real?” “How do I know something is true?” “How can I be a good person? and “If this is true, what else is true?” For ages 8-12. |

|

For graphic novel fans, see Michael F. Patton and Kevin Cannon’s The Cartoon Introduction to Philosophy (Hill and Wang, 2015). Chapters cover logic, perception, minds, free will, God, and ethics. A great introduction for ages 9 and up. |

|

Jeremy Weate’s A Young Person’s Guide to Philosophy (Dorling Kindersley, 1998) is a beautifully designed and illustrated collection of brief biographies of philosophical greats, arranged in chronological order, from the natural philosophers of ancient Greece through Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, to Descartes, Locke, Hume, Spinoza, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Sartre, and more. A second (shorter and non-illustrated) section provides additional information and discusses the various schools of philosophy. For ages 9-12. |

|

Dorling Kindersley’s gorgeously designed Children’s Book of Philosophy (DK, 2015) is an overview of philosophical questions and thinkers. Both are grouped into five categories: “Is the world real?” “What am I?” “Thinking and feeling” “How do I decide what’s right?” and “Why do we need rules?” For ages 9-13. |

|

By Corinne Hosfeld Smith, Henry David Thoreau for Kids (Chicago Review Press, 2016) is an overview of Thoreau’s life, times, and philosophy with illustrations, fact boxes, and related hands-on activities, among them making a journal, conducting a plant inventory, and writing a protest letter. For ages 9-13. See more resources for Henry David Thoreau. |

|

Daniel Tatarsky’s Cool Philosophy (Portico, 2015) is an attractively designed collection of philosophy facts from Aristotle on, starting with an illustrated timeline. For ages 10 and up. |

|

Jamia Wilson’s Big Ideas for Young Thinkers (Wide Eyed Editions, 2020) is a graphically appealing and diverse overview of philosophical questions both classical (How do I know I exist? What is justice?) and contemporary (Is race real? What is gender? What is imagination?). For ages 10-14. |

|

David White’s Philosophy for Kids: 40 Fun Questions That Help You Wonder…About Everything (Prufrock Press, 2000) categorizes forty discussion-provoking questions under the headings Values, Knowledge, Reality, and Critical Thinking. Kids ages 10 and up are encouraged to tackle such knotty problems as “What is time?” “Can you doubt that you exist?” and “Are you the same person that you were five years ago?” For ages 9 and up. |

For Older Kids

|

David White’s The Examined Life (Prufrock Press, 2006) pairs passages from famous philosophers with explanations and spin-off questions. Chapters include “Do We Really Know What We Think We Know?” (Plato), “The Sound of a Tree Falling in the Forest” (Berkeley), and “Technology: Servant or Destroyer?” (Heidegger). For ages 12 and up.

|

|

Jostein Garder’s Sophie’s World: A Novel About the History of Philosophy (Berkley Publishing Group, 1997) – a novel about the history of philosophy – has now established itself as a classic. Fourteen-year-old Sophie finds a message in her mailbox with a pair of questions – “Who are you?” and “Where does the world come from?” – and sets off on a long tour of western philosophy. There’s also an ongoing mystery and great twist at the end, but the book is somewhat dense reading in parts. For ages 13 and up. |

|

By Sharon M. Kaye and Paul Thomson, Philosophy for Teens (Prufrock Press, 2006) is a guide to questioning life’s big ideas with background from the works of famous philosophers, dialogues and thought experiments, activities, and discussion questions. For example, kids discuss whether or not lying is always wrong, what purpose art holds in the world, and what would happen if there were no government. For ages 13 and up. By the same authors, also see More Philosophy for Teens (2007). |

|

Stephen Law’s The Philosophy Gym: 25 Short Adventures in Thinking (Thomas Dunne Books, 2003) is an excellent resource for philosophical novices. The book is essentially an entire course in philosophical thinking; each short chapter deals with a different philosophical question, introducing key points of argument through a debate between, say, a vegetarian and a meat-eater, a human and a pair of visiting aliens, a serial killer and a judge, or a pair of philosophy students at the horse races. The debates are paired with “Thinking Tools” boxes (which contain helpful hints on the process of logical argument), expanded explanations of important issues, conclusions, and lists of what to read next. Sample chapters include: “Where Did the Universe Come From?” “Could a Machine Think?” “Why Expect the Sun to Rise Tomorrow?” and “Is Morality Like a Pair of Spectacles?” Law also demonstrates philosophical approaches to such topics as gay sex, the existence of god, creationism vs. evolution, designer babies, and moral relativism. It’s tough stuff, but it’s a thinking person’s meat. For ages 14 and up. |

|

Stephen Law’s Philosophy Rocks! (Disney Press, 2002) is the American version of the more elegantly titled British The Philosophy Files. Basically it’s The Philosophy Gym for a younger audience, ages 12 or so and up. It covers eight major philosophical questions, again in a clever debate format, with background information, descriptive examples, points to ponder, and cartoonish illustrations. Questions include “Does God Exist?” “How Do I Know the World Isn’t Virtual?” and “Should I Eat Meat?” A sequel, The Outer Limits (Orion, 2003), poses another eight philosophical conundrums, among them “Do Miracles Happen?” and “Why Do These Words Mean Something?” |

|

By Julian Baggini, The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten (Granta, 2010) is a collection of 100 short thought experiments for armchair philosophers. Discuss: Are you a computer simulation? If God is all-powerful, could he create a square circle? For ages 13 and up. |

|

Thomas Nagel’s What Does It All Mean? (Oxford University Press, 1999) is an excellent (and very short) introduction to philosophy for high-school-level students. In just over 100 pages, Nagel covers some of the major questions that philosophers grapple with, such as the mind-body problem, the meaning of words, free will, right and wrong, and – the kicker – the meaning of life. |

|

Philosophy, edited by David Papineau (Oxford University Press, 2009) is a lavishly illustrated and appealing written overview, with clear and interesting explanations of the ideas of famous philosophers. Chapters are World, Mind and Body, Knowledge, Faith, Ethics and Aesthetics, and Society. Excellent for ages 14 and up.

|

|

Ian Olasov’s Ask a Philosopher (Thomas Dunne Books, 2020) provides witty (and philosophical) answers to questions commonly on people’s minds – based on interactions with pedestrians on the streets of New York. “Do we have free will?” “Are people innately good or bad?” “What makes a boy a boy?” “What makes someone mentally ill?” “Should you kill baby Hitler?” And finally a useful bonus question: “What’s the best way to teach myself philosophy? How do I start?” For teens and adults. |

|

Also for older teenagers, check out the Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series, developed by philosophy professor William Irwin. Each book consists of a series of essays exploring the philosophical themes and questions inherent in popular movies, books, and television programs. Many titles, among them Mr. Rogers and Philosophy, Dungeons and Dragons and Philosophy, The Matrix and Philosophy, The Wizard of Oz and Philosophy, Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy, The Lord of the Rings and Philosophy, and, of course, Harry Potter and Philosophy. |

|

Philosophy-minded teenagers may also enjoy Philosophy Now, a quarterly periodical subtitled “A Magazine of Ideas.” It’s a philosophy magazine, rather than an academic journal – that is, what Discover is to science, Philosophy Now is to philosophy – filled with interesting articles, philosophy news (yes, there is some), book and film reviews, and more. |

|

The Great Courses has dozens of different courses on various aspects of philosophy, available as Instant Video, Instant Audio, or on DVDs. Sample titles include “Great Ideas of Philosophy,” “The Big Questions of Philosophy,” “Introduction to Greek Philosophy,” “Science Fiction as Philosophy,” and many more. Presented as a series of 24 or more half-hour lectures by college professors. Generally appropriate for ages 13 and up. NOTE: All the Great Courses selections periodically go on sale at greatly reduced prices. |

|

Philosophy Talk, “the program that questions everything,” is a podcast hosted by a trio of philosophers from Stanford University. Each week the team discusses topics that range from popular culture to morality, social issues, the human condition – and much more. |

Plays and Movies

|

David Egan’s play, The Fly-Bottle (2003), is the story of a confrontational meeting in 1946 among three famous philosophers – Ludwig Wittgenstein, Karl Popper, and Bertrand Russell – which legendarily culminated in Wittgenstein threatening Popper with a poker. If it comes to a theater near you, take your teens. |

|

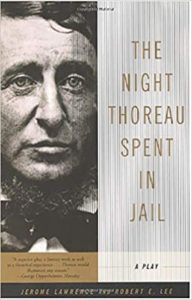

By Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee, The Night Thoreau Spent in Jail (Hill and Wang, 2001) is a dramatic account of Thoreau’s famous act of civil disobedience, when he refused to pay taxes in protest to the U.S. government’s involvement in the Mexican War. For that, he was thrown in jail. The play has a wider reach, covering Thoreau’s life, beliefs, and philosophy. A wonderful read for ages 13 and up. |

|

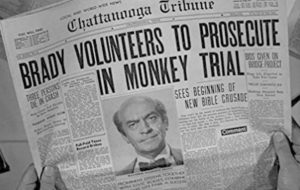

By the same authors, see Inherit the Wind (Ballantine, 2003), the fictionalized account of the 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial,” and the clash between legal giants Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan. The theme of the play – other than the obvious conflicts between religion and science, belief and reason – is the right of the individual to think his/her own thoughts. The superb movie version of Inherit the Wind (1960) stars Spencer Tracy and Fredric March. Not rated. |

|

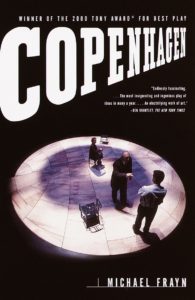

Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen (Anchor, 2000) is the imagined story of the 1941 meeting in Copenhagen of physicists Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg – who found themselves on opposite sides during World War II, both working to create an atomic bomb. It’s an imagined story because no one knows just what went on at that meeting between the two men – but in playwright Frayn’s hands, it becomes a debate on ethics and morality. It’s also a great supplement for physics students. |

|

Mindwalk (1990) is a wide-ranging conversation among three characters: a physicist who has just left her job after discovering that her research was being used for weapons development, an American politician who just lost a major election, and a poet. Political and social problems are approached from their differing perspectives as they wander around Mont-Saint-Michel, France. PG. |

|

Examined Life (2008) is a documentary subtitled “Philosophy in the Streets.” Famous philosophers and thinkers discuss their theories and ideas while visiting places of particular resonance for them and their ideas. (Cornel West, while driving through Manhattan, compares philosophy to jazz and the blues.) Not rated. |

|

In My Dinner with Andre (1981), two old friends – played by Wallace Shawn and Andre Gregory – meet for a meal and discuss the meaning of life and their very different worldviews. PG. |

|

Matt Whitlock’s Essential Movies for a Student of Philosophy covers 45, with synopses, reviews, and trailers for each. |

|

|

The Guardian’s I Watch Therefore I Am discusses seven different movies – each reviewed by a different philosopher and each covering a key philosophy principle. “How can we do the right thing?,” for example, is the theme of Force Majeure (2014); “What makes life worth living?” is the theme of Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946); and “Is there more to us than biology?” is the theme of Gattaca (1997). |